First Language, 2024

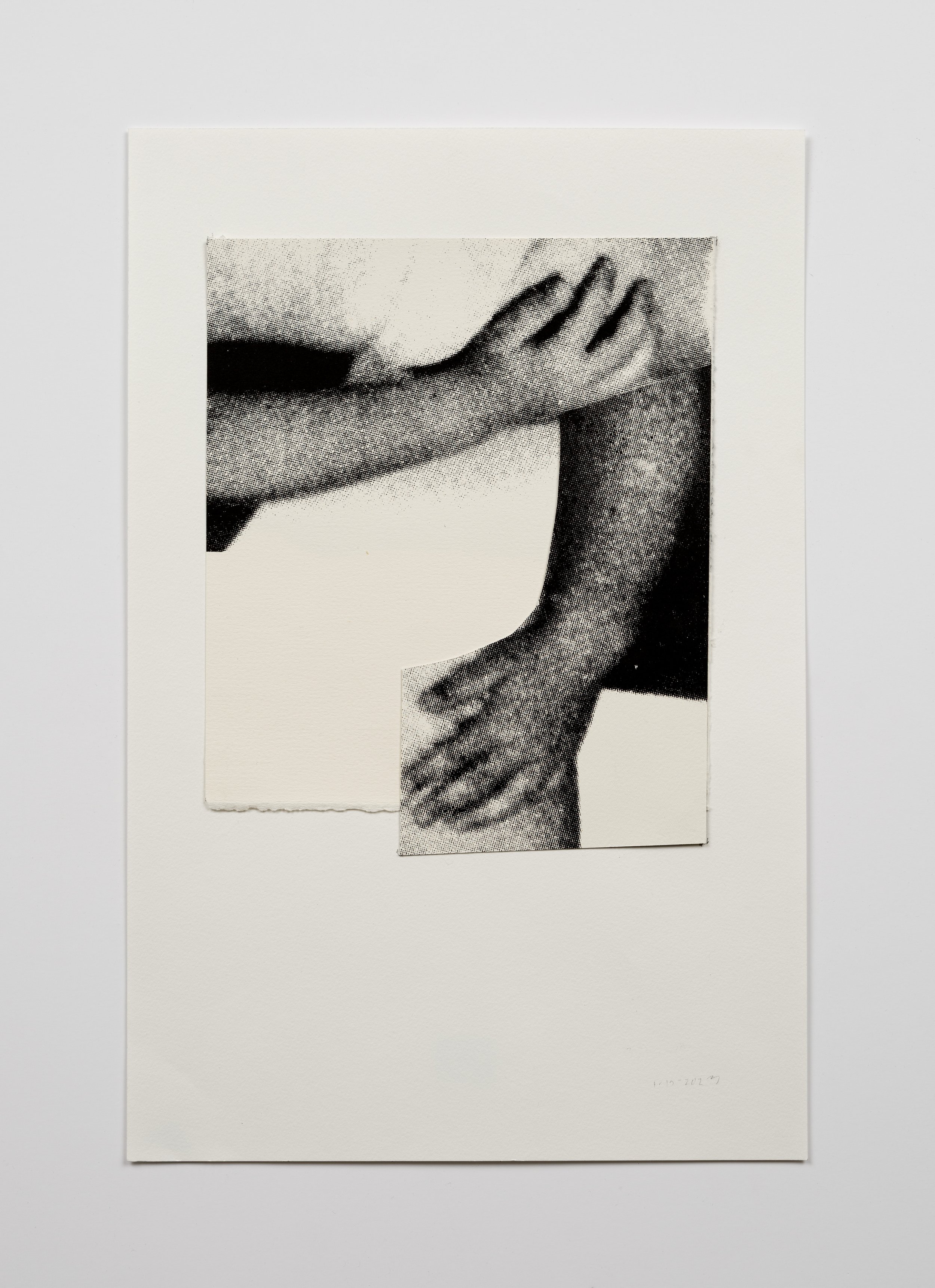

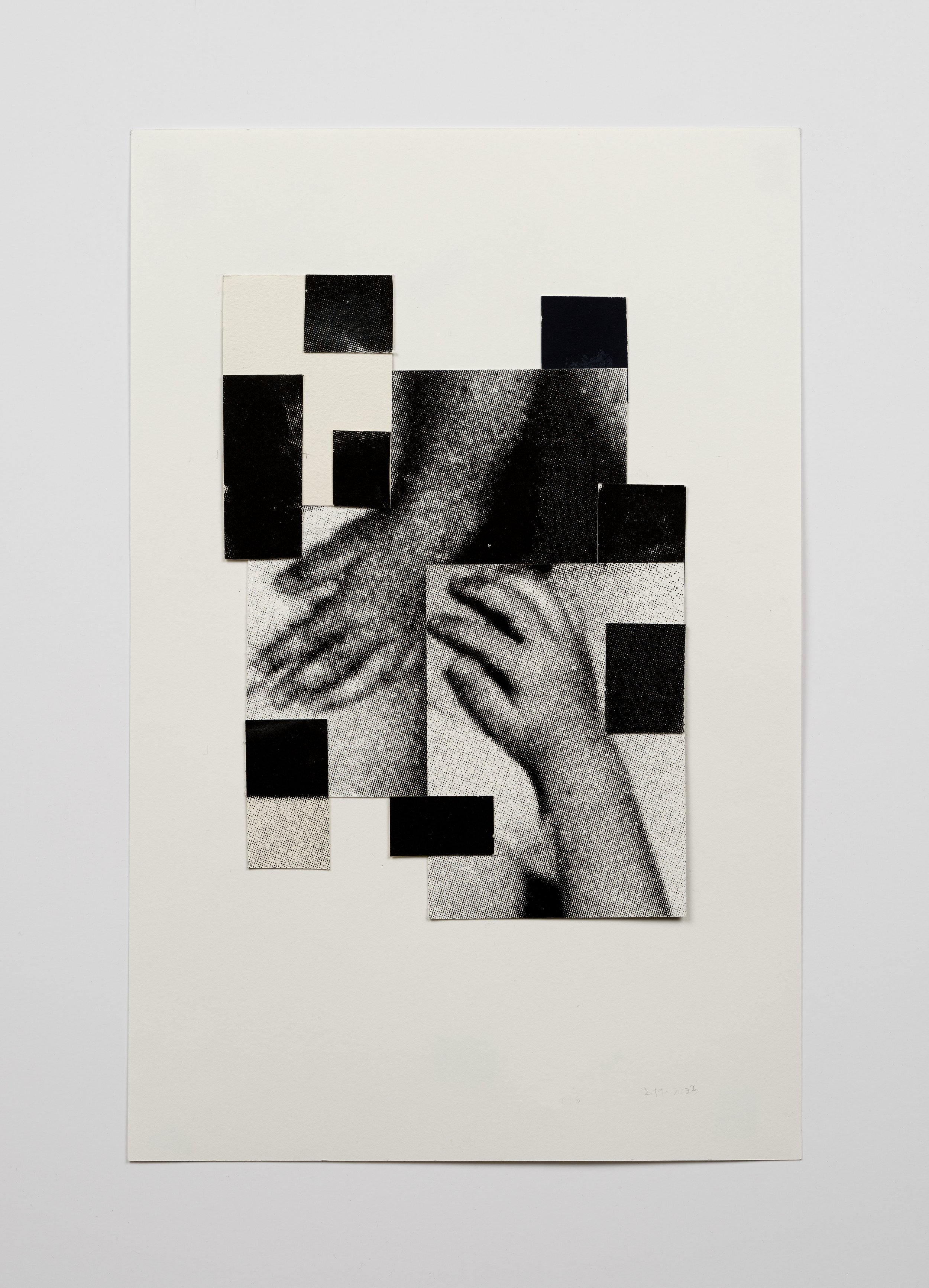

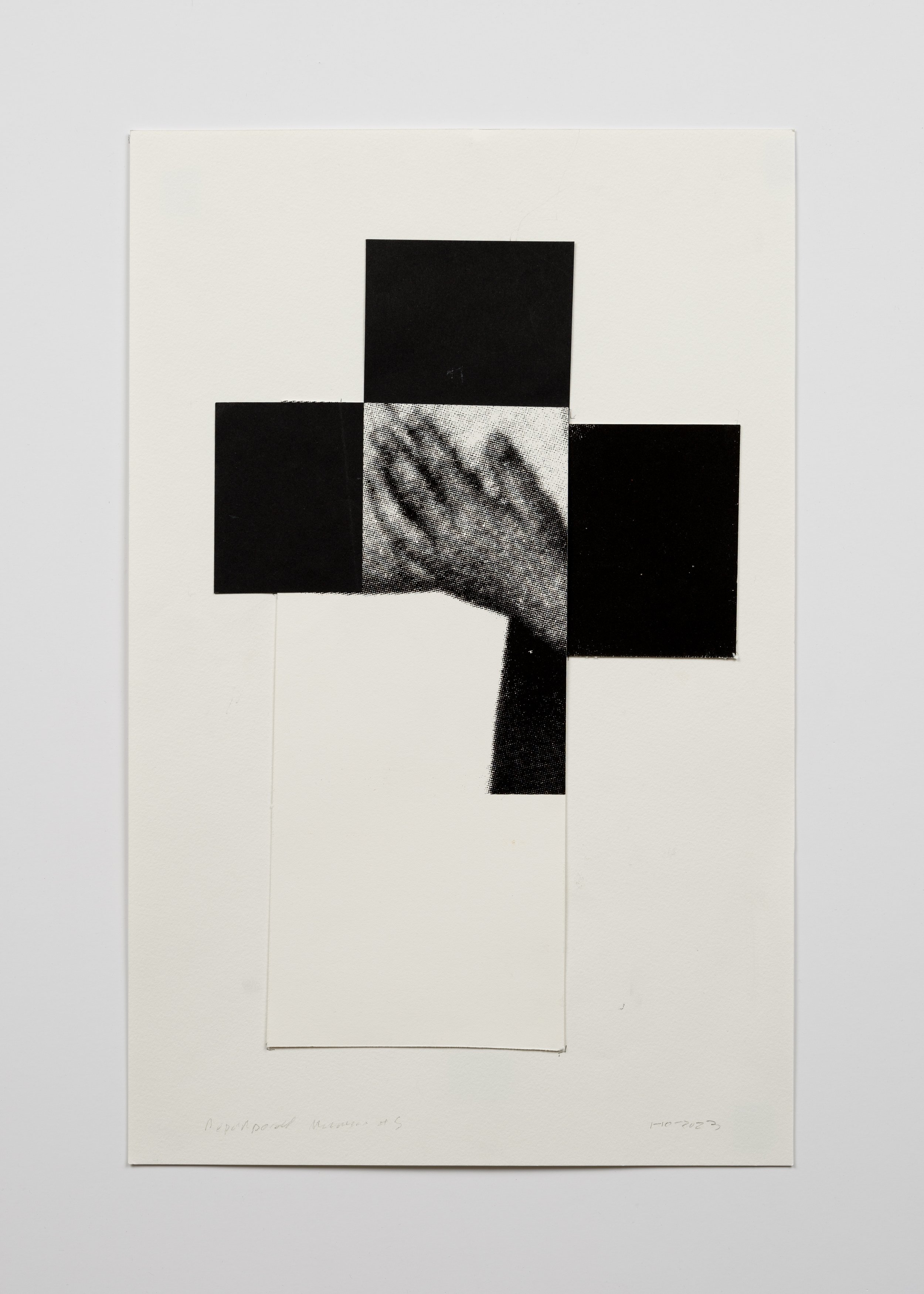

I began First Language by revisiting some old printed proofs of photographic silkscreens I’d done years before. In salvaging fragments of this earlier work, I saved a pair of hands. From there proceeded a series of works on paper, all in an elongated rectangular format, 17” x 11”. In these images, individual and unmatched pairs of hands are collaged and juxtaposed with geometric forms. It has always been my belief that touch is our true first language. For me, pictures, too, always precede words.

This title, First Language, refers not only to this series of collages, which I was invited to show at Five Myles, but also to the exhibition incorporating the collages with recent UV-printed aluminum sculptures. The show was on view 24 hours a day, through the month, allowing the pieces to incorporate shadows and the ever-changing light. Aluminum models and works on paper filled the gallery’s large interior space. The exhibition closed with a talk with the critic Richard Vine (below), and a poetry reading with Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Jennifer Firestone, and Kimberly Lyons.

First Language I (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language II (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language III (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language IV (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language V (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language VI (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language VII (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language VIII (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language IX (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language X (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language XI (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language XII (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language XIII (2023). Photographic Silkscreen with Paper. 17" x 11"

First Language Installation, Five Myles Gallery, 2024. 40' x 12'

First Language Installation, partial view. Five Myles Gallery, 2024. 40' x 12'

Debra Pearlman interviewed by Richard Vine, at Five Myles Gallery exhibition First Language 7-16-24

Richard Vine: Well, I'd like to start by being very grand. As we look around at your work, I'd like to put it in a historical context and argue that it's part of the reclamation of figurative art after it was hijacked by fascism in the mid-20th century. If you go back to the beginnings of Western art, the glory of Greece was largely a depiction of the figure. And that fascination carried right through, even in Gothic art, with more clothes, etc. And it was really only after figurative art was hijacked by the Nazis and the Soviets and Franco and Mao in the mid-20th century that the art world became skeptical about it. And for a while, as you know, you sort of had to be abstract to be fashionable and cool and cutting edge. But now, thank God, thanks to people like you, we have figurative art coming back in great strength. And I think in your case, it's influenced by some particular people, but I haven't heard them mentioned in conversation with you. You and I have known each other since the dawn of time in Chicago. And when I look at this work, I'm reminded of a couple of things that were very big in Chicago in those days. One was street photography with people like Aaron Siskind and Arthur Siegel. And the other was the Chicago Imagists, the Hairy Who, who dealt with the human figure in a very confrontational way, often fragmented, often distorted. I wonder if you could talk about that. Was that a conscious influence on you at the time?

Debra Pearlman: Absolutely not. When I went out to Chicago for grad school, I hadn't been as far west as Pennsylvania, so I was pretty sheltered. Being in Chicago made me realize how East Coast I was. There it was minimalist stuff, which was hard to digest. When I was an undergraduate, the few people doing figurative work were torn apart as “Sunday painters,” totally dismissed. The Imagists were kind of shocking. Their work had no texture, it was so flat and poster-like. The word of the day was “obsessive.” Karl Wirsum was one of the Imagists, now getting a fair amount of attention. His daughter Ruby Wirsum became my babysitter. I looked at Karl's work. And I think that living there, about 13 years, I did start painting images when I was in Chicago, but very textured, limiting the palette, images similar to what you see now. I think about the Imagists in hindsight because I didn't respond to them at the time. But it's interesting, as a comparison, I think. So yes, I have taken from both those worlds. And I do think that when I veer off to more abstract form, so there's just a hint or fragment of an image, I start to feel like I'm falling off a cliff. I need something a little grounded that has content that drives me in some indirect or direct way. Some abstract work for me looks very arbitrary. It's obviously not for the person who makes it. When abstract work is good, it's brilliant. I have a passion for it. I just can't live in that world full time.

RV: I think you were also friends with Leon Golub and Nancy Spero. I would think that Nancy would have an influence.

DP: Yes. They were very special in our life for a long time. And I'm grateful for that relationship. They were very supportive, very giving, and people of real conviction in every way in their life. And we see that in their work. They did not compromise at all.

RV: Their artwork was also pretty highly political. That's not a path you would take in, at least on this part of your work. I can tell.

DP: Sure. But there's a project this fall happening that I'm not quite ready to talk about, but it's a public art piece that will be going up around voting issues. I'm guessing that people in this room might be as terrified about the election as I am. It's something that I've been wanting to do for the last elections, plural. I think that sometimes the work that I'm drawn to, the images that I use as social material, my photographs, have to do with a kind of vulnerability that is certainly a social and political issue in our culture. But it's not something I'd want to bang over your head.

RV: You'll start to see the two extremes right here, an almost straight photograph on the wall, and then this highly worked sculpture. Can you call it a sculpture on the floor.?

DP: You can.

RV: Photo sculpture. So how did you go from there, that sort of thing, to this sort of thing? And why?

DP: Well, it's the gestures that capture my attention, and that's what I continue to shoot, the formal quality, the movement, what that movement looks like. The image was so strong in the photograph, the way the figure looked and how she was caught in space. I got rid of all the background information, so the figure just looked like it was floating or falling. I like that ambiguity, that you just don't really know. It could be threatening, it could be joyous, it could be any of those things. When I prepare, I always make a paper model for scale to make sure that it's making sense, and what I want before I go through my whole process of painting and so on. When I was preparing for my show here last fall, I did a preparatory cutout of the boy that's hung in the front (Fall 2), I cut it out, and when it fell to the floor, I realized that that's what it needed to be, that the boy’s gesture that I was initially drawn to could be enlivened by making it physically in space. I started working in metal.

RV: Can you just sort of walk us through the process, technically?

DP: Sure. First, the photograph: Once I have the scale and the gesture that I'm after, it's printed. I then work with paper prints to play with that three-dimensionality. The images are uv (ultra violet) prints on aluminum. It's printed flat, and then it's cut out. Though I have the equipment to cut it, the computer is equipped to do that more precisely. We then get to bend it according to what the aluminum allows in relationship to what I want to do. It's a dance that happens. Aluminum doesn't bend the way other materials do. You can't make a compound bend for example. You work with the image, and then things happen from that process, which is a nice discovery. Sometimes the pieces crack, and that's fine too, because the fragments are interesting to me.

RV: I mean, it ties into the very long development in our history in this attempt to convey motion in a still image. And I can do it with some grand gestures, - it's very clear that the hand is moving from here to there, and the futurists did it doing multiples... And Muybridge came along and gave us the photographs. But now we live in an age of moving images.

DP: I don't do that.

RV: Let me ask you , we have the image. Why bother?

DP: All I can tell you is that that's a boundary that I have, that I don't have any interest in crossing. It's logical to make a film, but I'm not that person to make that. I need to use my hands. It's a physical process. That's how I think : with my eyes and my hands. I think in pictures. That's why we put things together. The idea of making a film- it's why I don't just shoot photos. It's too technical. I want the interaction of physicality, to do something with it somehow, and to read it in some other way. But, I also have printed photographs, and I show them, and they stand on their own. It's not enough for me.

RV: Also, doesn't the arrested image tell us something that we don't get if we just see the figure of motion? We just saw that's a real child spinning around. It's not the same as seeing that innocent child in time.

RV: Right.

DP: And that's a choice. That particular instant of seeing and choosing to shoot is my choice of what I care about, of what I'm seeing. Over time, I see how much consistency there is in that. You asked about Chicago. I remember that I took a class with Harold Allen, who was a well-known Chicago architectural photographer. It was the year before he retired. He was this gentle, small man, very patient, and very serious. I wanted to take a photo class. They weren’t offered at the university. I remember getting so frustrated in the dark room that no matter what I did, there was always one little piece of dust. I could be in there for days or weeks, and they would always be one little piece of dust. I was so aggravated. I got a brush and I painted the developer. The photograph looked like a puzzle. And I thought “That's more interesting”. I showed it to him, and I still remember this gentle little soft-spoken man saying, “Well, it's nothing I would do.” [LAUGHTER] He was a real technician.

RV: But let me ask you about the moments you do choose. Because they really seem to teeter on this knife edge. Because it's joyful, and yet their distortion suggests violence almost.

DP: It's true. I am interested in this. There's some meat there. You don't know where it's going to go. I can't really describe it. It's a very visceral reaction. And then you asked about Leon Golub. Leon talked a lot about going to the edge of something. And maybe that's part of what that is, where something can be multiple things. That ambiguity, for me, is what makes art interesting. It's not a poster with one idea, telling you one thing. It's not dogmatic. You have this ability to come at it in different ways and to have multiple kinds of experience. The more that this happens, the more it can resonate and have more potential as an image to live in the world.

RV: One of the things that is interesting about the images is what they don’t do. Because so many of the figurative images in the past were selling us something. They were selling us an idea or they were selling us a product or they were selling us a personality. And this doesn’t do any of those things and very intentionally so.

DP: It's also important that in that split second I try to avoid seeing the face, because it's not a portrait. The specific identity doesn’t matter. It's about the gesture and the way that body looks in motion because that elicits a more universal response.

RV: So why, say 95% of the time, have you completely eliminated the parent?

DP: I did do a show called "Unaccompanied." Children by themselves are in another kind of world. There's an honesty and a spontaneity that adults don't have in public. People walking by are looking at phones, carrying their coffee, walking their dog. Their body language is pretty limited. A kid jumping around is a free-for-all dramatic show with all this life and action. But there’s a dark side to that too. I think about that. After the election of the one I don't want to name, when I was just coming to the end of my teaching positions, behavior in the classroom became hellish; all pretense of civility in a class just stopped. It's the only time I ever walked out of a lecture in 30 years of teaching. The students were so rude and horrible. I thought, What drives them? These young people grow up and become adults. Maybe it starts in the playground with the bully and the followers and the kid off to one side, and you see it all in all the images you have made.

RV: You talked earlier about the artistic impulse to take it to the edge. It seems to me that children do this all the time. It’s always like: “scare me Daddy” or “let's see how high up I can go and jump off and still not get hurt” or “swing me around until I throw up”. [laughter] Maybe there's a little affinity there every time the child and the artist's personality are just so wild.

DP: Are you asking me which one I am? [laughter] I'll just let that pass. [laughter]

RV: At some point we have to deal a little bit with subject matter. [laughter] They are all children. And that's become a very sensitive area. Maybe you should just about how you deal with those new concerns that are always happening.

DP: Well, one of the things I say when people ask me where I see these children and why I am drawn to them: Well, it's my height. (laughter) This is where I live. They’re at my eye level. This is what I'm looking at. The action and activity appeal to me, how people interact and behave. We're living in a pressure cooker of behavior. Out in the country, people smile at you even if they don't know who you are. Here in the city, you're taught, “Don't see that.” These are cultural ways of behaving. I'm always noticing these moments, these fragments. I squinch my eye and I see them in space. That made photography more central in my work than drawing, which I miss, but drawing doesn't communicate in the same way.

RV: But some of the people who helped reframe figuration from politics took it in a direction that is now considered very problematic. In Chicago you had Henry Darger, who was an outsider artist, who wrote an enormous illustrated epic, about the seven Vivian sisters who were constantly under threat of being carried off as child slaves. And in contemporary practice we have Sally Mann. Do you feel yourself being censored in a way, self-censored?

DP: We're living in a time where street photography is not what it was. The type of street photographer who would accost someone on the street and put the camera two inches in front of their face wouldn’t survive in the world now. It's not how we live. Not all of us want our images on social media, and we have the right as adults to decide about that, even if a picture was taken in a public space where permission is not needed. I've taken good pictures that I would not show publicly because they are disturbing. One of them is of a child in blackface. I doubt that she thought much about it. She probably was pretending to be a witch, but that image is not something you can put out in the world, knowing that it may reflect badly on someone.

RV: Having done a lot of work in China where they had outright censorship, it's always seemed to me that the most damaging thing about censorship is not just what's blatantly imposed; it's when the artist becomes aware that there are certain places you cannot go, certain things you can't think. And after a while, you're no longer aware that you're not thinking about them. And that's when the censors have really succeeded. And I worry sometimes about a climate of sensitivity. Maybe we're shooting ourselves in the foot.

DP: Are you seeing that?

RV: Well, you know, the novel that I published there’s a 12-year-old character, and then I got some feedback. [laughter] I'm suggesting that the treatment of the presentation of this very curious child was inappropriate. It was clearly suggested that I was a pervert, so I'm going to start here.] There’s also a predicated notion of child innocence. That’s a word we don't hear anymore. [laughter] I worry that we can no longer trust the climate. That's actually the moral of it.

DP: I think that is some of the time that we're living in. This is not the first time this has come up in a public conversation about people in various positions in the world. What are we not going to see by gay people for those reasons? There was a prominent legal case against a wonderful photographer, Arne Svenson, who shot with a birding lens to make images of windows in a high-rise apartment building. I haven't seen many photographs as exquisite. Some of them showed children or young people. You couldn't identify anyone in the photographs. There were shadows or curtains that obscured the figures. You never saw the face. He won the case because views from outdoors are in the public domain. When I went to see his exhibition, however, the picture of the child that I thought most extraordinary wasn’t there. I don't know if the omission was his decision or the dealer’s. It bothered me that that photo was not in the show.

RV: Do any people have questions?

Question from the audience: I just wanted to say that you referred to what you're doing as graphic sculpture, as if they were crossing a boundary between two mediums. I wonder if that's something you could talk about and whether that issue, boundary crossing between mediums, is something that people still care about.

DP: Yes. I remember that when I was at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the museum held an annual Chicago and Vicinity Show. I submitted a charcoal drawing on fabric. They called me and said: “We want it, but we had a meeting. We decided that the definition of drawing is that it has to be on paper. Will you remake it?” Well, you can't really remake something. It becomes something else on a different kind of substrate. It was bizarre. These categories still don't make sense to me, but museums lived by them. Nancy Spero actually was so upset that she called her large works on paper “paintings” because painting has a higher status than works on paper or prints. The paintings that I have done in recent years are photo-based and silk-screened. I always combined these areas. And I've always worked with collage. Again, spatial quality is essential. I'm interested that the photo printed on aluminum, when it bends, keeps changing as light hits it. It keeps changing. And you don't know whether spatially it's a shadow or a three-dimensional object or the photograph of one; it's confusing. I like that, that it's not so clear. You could just put a print on a piece of anything and change its shape, but then it's something else.

Q: You just mentioned something I was going to ask you about, the little shadows in these images. And is that something you're interested in? How do you think about it?

DP: I love the shadows and how the sculptures interact with light. I love that that light adds to the physicality of the work, and that it can change over a day. In my show at the Catskill Art Space, there was direct light from the window at certain times. The first morning I went in, the sun was hitting one of the works at just the hand and the wrist. Suddenly, that part of the work had a yellow-golden light, like Caucasian skin, but the rest of it was blue—like metal. So that's what morning light looks like. I've never seen them like that in the studio, or the shop. When I was sandblasting photos in glass, strange things happened with how light was received and refracted and gently changed… It just adds more space.

Q: Are the kids aware of you with the camera?

DP: Mostly not, after a picture is taken, sometimes. We all know that if you know you're being photographed, the response changes. That's the conundrum of taking pictures outside. You want to ask permission, but even if permission is given, you won't get the picture you wanted.

Q: So what do you do?

DP: Permission didn’t used to be considered necessary. Now it is by many people. It goes back to that same question about how you deal with this inside-outside world. But because part of the magic of seeing these moving bodies is their lack of self-consciousness, I think you have to take the risk but obscure their identities if possible. It's like they're living their interior life in a public space. And that's why there's so much life in those movements.

RV: Have you shot in other countries?

DP: These were from Cuba.

RV: Did you see any cultural differences in one group?

DP: I think they were having more fun than a lot of Americans. They were not as restricted whenever I saw them.

RV: I see tension in the work: is the child crying or is the child falling, or is the child free? Is there a coercion? There is a hand holding the child, and I can't remember how that plays with the fact that it's a child.

DP: There's an incredible line, in Shakespeare's A Winter's Tale. Leontes (?) is talking about the passion he has for his child - that he can be beyond furious and beyond in love- talking about those extremes. The first time I heard this speech, I was mesmerized, because I thought it was the most honest thing I'd ever heard. How do we have those strong emotions? The other extreme is really feeling nothing.

Q: I was just wondering about collaboration, that particularly with the historical record, and sculptures, and did that have anything happening in the future?

DP: I really am thrilled to have been able to do this, because when you develop a relationship where someone can see what's in your brain, and they have the knowledge to realize it, or the strength, or whatever, it's magic. I mean, it's your work, but you're getting to take it to a level that is impossible for me. I mean, I can cut metal and use a metal saw. But it's not the same. I feel the balance with solitary time in the studio, which I also treasure, and this is just perfect. It's like a seesaw, just really one to the other. I feel really lucky to have that. Thank you.

Q: Besides all these sort of kids at play, have you photographed athletes?

DP: I have. The athletes are not so interesting. They're very rigid and geometric. At least that's been my experience so far. I would like to shoot dance. So this is a thrill and honor to have this last show, to say goodbye to this space. So many people have come through here. It's such a pleasure to see this wall. Hanne Tierney said you have to do it for the pleasure of it. Thank you. (audience applauding)