Roundabout, 2023

How do the power struggles inherent in the games we play as children affect us in adulthood? Why do some become followers, others leaders? How do traits — such as confidence, regardless of ability — become legible through gesture and other physical language? These questions have long preoccupied me; lately, in our politically divisive moment, they have felt particularly important.

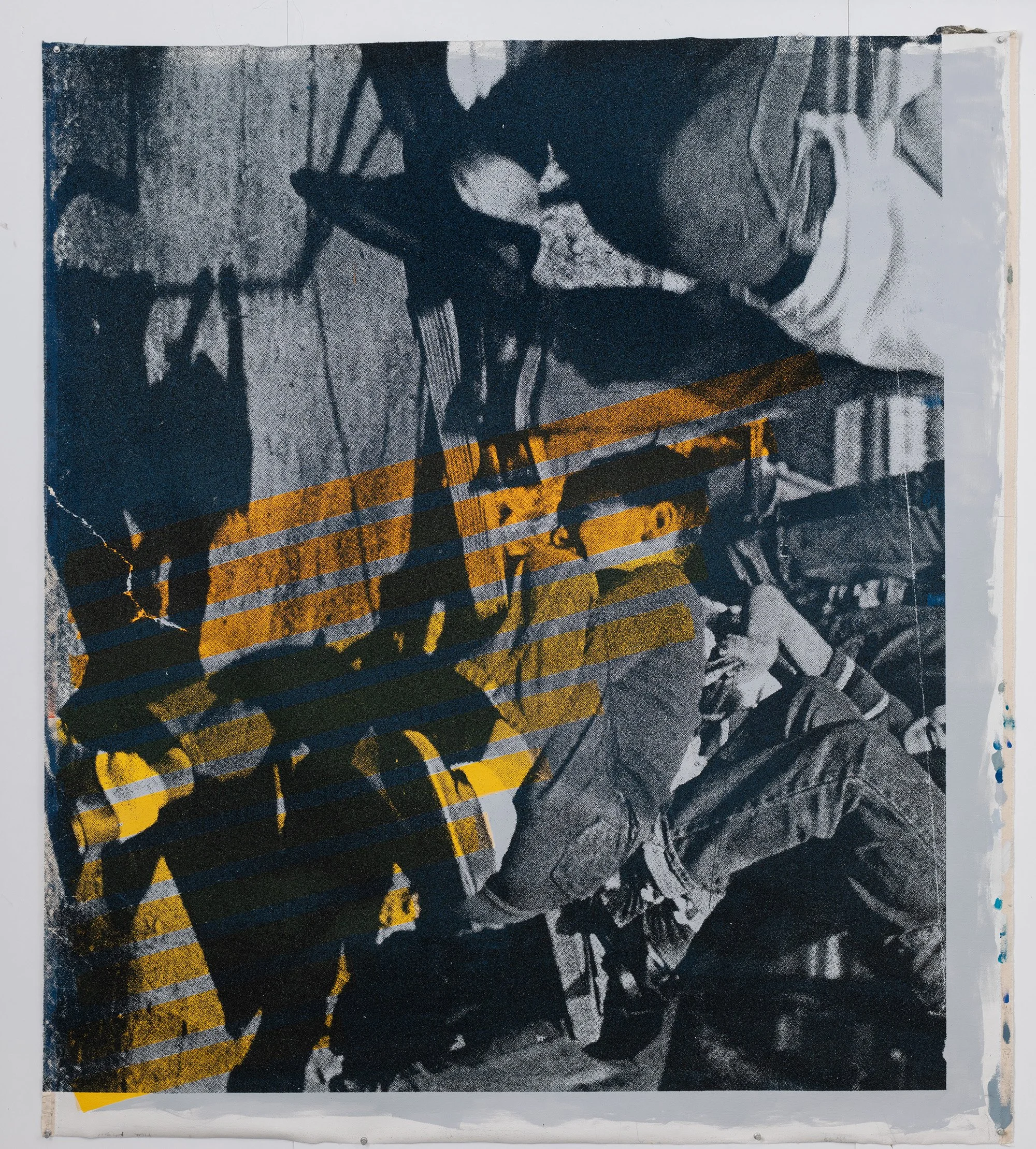

In my image of boys on a roundabout — reminiscent of Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware, the most visited painting at The Metropolitan Museum of Art — it is clear who is in control. The larger, taller figure on the painting’s left side leads the group, as Washington does. Power dynamics play out among children in everyday moments like this one, mirroring those in the adult world. The boys enjoy the moment, grabbing on. Variations, suspended like tapestries, reflect a time of possibility and potential.

Pieces from this project were exhibited in a show of the same name at FiveMyles Gallery in 2023, with a catalogue essay by Nancy Princenthal (see below).

View Roundabout, the Exhibition

At FiveMyles Gallery, September 9 - October 15, 2023

Debra Pearlman: A Substantiation of Shadows

All that glitters is pitch dark in Debra Pearlman’s photo-based paintings, where joy rains down in buckets, along with sorrow and shame, each state mitigated by an innocence that is itself cast in doubt. If the changeable emotions of the children all these paintings feature travel a mobius-shaped circuit, the work’s constituent materials and processes, source imagery and formal underpinnings, are similarly deployed recursively. Pearlman’s methods involve complex sequences of fragmentation, layering, substitution and repetition—like dealing out Tarot cards, she says.[1] It is a matter, Debra further explains, of using reproductive techniques and regenerative imagery to get at the business of really seeing children—and, she doesn’t need to add, the people they grow into.

Expulsion, for instance, is based on a still from a film Pearlman took nearly forty years ago. It shows two girls, both soaking wet, their heads bowed, walking away disconsolately from the water’s source, which is an (unseen) open fire hydrant: summer in the city. Expelled from a concrete garden of Eden, the girls are shadowed by a glinting black shroud of Magma [is this a commercial medium?], a viscous medium that Pearlman’s often uses and which, like the semiliquid subterranean rock of the same name [?], is imbued with tiny glass beads. It is applied to surfaces already painted in primary-colored geometric configurations, over which photo-silkscreened images are printed, in deep blue; lastly, Debra selectively scrapes away the Magma. (Expulsion’s support is canvas; elsewhere she has used acetate, paper, others textiles and, for new work, aluminum.)

The Adam and Eve of Masaccio’s renowned quattrocento fresco Expulsion are echoed with striking precision in Pearlman’s painting of the same name (albeit without Masaccio’s glorious avenging angel); so too does Bernini’s bronze St. Teresa in Ecstasy, paragon of Baroque psycho-sexual religious fervor, inevitably come to mind before Pearlman’s The Carousel. In this painting, a small blond girl is seen seated on a carousel’s charging horse, her head thrown back and her eyes closed. A man lurks behind her, his face blocked by hers, his arm around her waist; though the gesture could simply be a father’s, steadying her, this shadowy figure feels unmistakably sinister. The impression is the stronger for the intensity of the child’s expression, which conveys a psychological transport that is profoundly discomfiting.

Religious symbolism is evoked again in Looking Down—Pearlman jokes that she is an honorary Catholic—which pictures a girl, again drenched, her arms outstretched before her, palms up and illuminated a little uncannily, as if she is receiving stigmata. Several paintings derive from a photographt that Debra took shortly before Covid of a boy walking gingerly along a fallen tree trunk. His balance is tentative, and his uncertainly outstretched arms suggest, the artist says, a connection to Icarus, but also to a slightly wobbling cross. In another version of this image, the surface is dotted with further crosses, which allude to Red Cross medals given Debra’s great-grandmother (and namesake) following World War I. An additional association, unintended but welcomed, is to Mondrian’s “Pier and Ocean” paintings, with their fields of small crosses and dashed lines. In a couple of paintings based on this photo, the underpinning rectangles of color make it seem the boy is signaling with flags.

Elsewhere, religious symbolism gives way to politics, with more explicit references to flags, specifically American ones. Red and white horizontal stripes appear in a series of paintings called Roundabout (which also names this exhibition), where they underly variously cropped images of boys on a once-commonplace type of playground equipment. Long since banished for its hazards, it was simply a big wooden turntable with metal poles, powered by children running alongside it and then jumping on and grabbing ahold, while other kids kept it going before leaping on in turn. In the original photograph, borrowed, Pearlman recalls, from either Life or Look—and invoking the ethos and esthetics of the 1955 MoMA photo exhibition The Family of Man, a dubiously utopian paean to a global harmony—one boy faces the camera squarely. His posture, supremely confident and commanding, led Debra to associate him with Washington crossing the Delaware in the famous painting by Emmanuel Leutze. In the fragment taken for this exhibition’s Roundabout paintings, all faces are eliminated; only the boys’ legs and feet are visible, churning like the drumbeat of human and equine legs on a classical Greek frieze—an army on the move. One version of Roundabout, without red stripes, is tipped sideways into a vertical composition, so the boys seem to be cascading down, perhaps euphorically, perhaps catastrophically. Uncertain, too are the gender dynamics in Pearlman’s work. “Everything comes down to a power struggle,” she says of the relations between boys and girls that her work addresses; in this exhibition [or, in one plan of the exhibition, they were to], they face off on opposing walls. As such an arrangement [would] makes clear, the boys are generally (although not always) the more aggressive; the girls are alternately buoyant and abashed.

Other oppositions in play include those between subjects and the camera. Children seldom pretend to ignore it, as adults do; indeed, they can vamp for it unapologetically. At the same time, they are capable of complete obliviousness—another way, inadvertent but potent, to challenge the camera’s command. A related dynamic concerns what the camera sees, and what is off frame but nonetheless felt. Lucy Lippard, writing about photographs of children by women, notes that many took up cameras within the Settlement House movement to document the lives of immigrant families, and flourished when photography was not yet established among the fine arts; institutional embrace cv coincided with domination of the field by men. Addressing a wide range of images, Lippard singles out Diane Arbus’s of a crying baby, its face wet with tears. Wringing its hands in a disturbingly adult gesture and looking off to the distance, the baby seems to be seeing the future.[2] But its complete self-involvement is also striking, and is something Pearlman also captures. Whether by framing or cropping, or by simple circumstance, she seldom pictures children looking at the camera—that is, at us. Partly that is out of caution. It is not today permissible to photograph identifiable children without consent. But it becomes a crucial aspect of the work, which explores internal experiences, even when they involve public or social encounters.

Further to the question of what—or whom—the camera sees, it is as a rule women who are implicitly the absent figures in photographs of children at play. Whether Helen Levitt’s wry photos of kids on their own, navigating mid-twentieth-century urban life, or Sally Mann’s of her daughters, pictured as sylvan nymphs, the children’s independence is conditional on an invisible (and perhaps displaced) maternal guardian; the same is true of Pearlman’s. Debra says she was strongly affected by Garry Winogrand’s contention that in a figure-based scene, the questions “what do you see, and what do you not see” are equally important. Writing about the blurry but psychologically acute pinhole photography of Barbara Ess, Michael Cunningham similarly suggests that in her work, “whatever lies immediately beyond the camera’s range is as much a part of the picture as that which the camera was able to apprehend.” Further, Cunningham says, in conveying that by the time the shutter is released, Ess’s subjects are “already somewhere and—something—else,” she affirms that “a photograph, any photograph, is simultaneously a record of a subject and a disappearance.”[3] As Roland Barthes put it, realists (of whom he considered himself one) “do not take the photograph for a ‘copy’ of reality, but for an emanation of past reality: a magic, not an art.”[4]

But Debra is not simply a photographer; almost all the work in Roundabout is properly termed painting. Like Katherine Bradford, whose narrative paintings begin with the disposition of highly colored, loosely rectangular shapes on canvas, Pearlman’s work is grounded in formal as well as figural choices. Further, Pearlman’s paintings are highly tactile, their layered surfaces a complex landscape of texture, light and color. Not infrequently, Debra undertakes fully three-dimensional objects. At present she has begun screening photographs onto brushed aluminum, as in a sculpture bearing the image of the tree-trunk-walking boy, here twisted, flattened and flung to the ground in a graceful, quietly mortal collapse. A new accordion-fold book features images of boys with capes, and is called False Freedoms; as with all artist’s books, it is a kind of time-based work, and a sculptural one. At the entry of this exhibition is a small photo etched on cloth showing the face of a girl with downcast eyes, sheltered by a black coat pocket that was extracted from its source, stitches still visible: a shadow on the back of a cave. Even Pearlman’s flat works are sculptural: Debra refers to the paintings as tapestries, because they’re so substantial. However much they are obscured, cropped, decentered and adrift in washes of texture and color, Pearlman’s subjects, too, have the presence of fully explored three-dimensionality.

—Nancy Princenthal

[1] All quotes of the artist are from a conversation with the author, June 7, 2023

[2] Lucy Lippard, “Brought to Light: Notes on Babies, Veils, War and Flowers,” in Defining Eye: Women Photographers of the 20th Century (St. Louise Art Museum, 1997), p?

[3] Michael Cunningham, “Dark Matter,” in I Am Not this Body: Photographs by Barbara Ess (New York, Aperture, 2001), 68

[4] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (New York, Noonday Press, 1981), 88